Plants produce dyestuffs that give deep, vibrant colours or subtle shades to textiles, paper and wood. Natural dyes from plants, and from fungi, earth and insects, have been grown and used for thousands of years, and despite the dyeing industries being overtaken by mass produced synthetic pigments, the natural dyes are still part of many local traditions, especially in tropical and sub-tropical regions.

There is little evidence of the broad-scale growing of dye plants in the croplands here before the last few centuries. As crops they are no longer familiar here, yet the art and science of using natural dyes remains in manufactures and craftwork.

The Plant dyes pages at 5000 Years consist of the Summary and Introduction below on this page and the following links –

- Dye plant species of the world – notes on their biology and uses (under construction)

- Dye plants in the Croplands – past, present, prospects

- Sources, references, links, contacts – and ideas for activities and visits.

Dye plants – summary

- Plant dyes have a long history in the croplands going back thousands of years.

- Few dye plants have been grown commercially in fields here – woad in places, weld and occasionally madder – but many plants have been and are still harvested from the wild for small-scale commercial production or craftwork.

- Elsewhere in the world, dye plants have been grown profitably as crops. The tropical indigo, old fustic, brazilwood and red sorghum were grown abroad, imported and supplanted in many cases our home-grown dye plants, until they were in turn replaced in the 1900s by manufactured pigments.

- Rich traditions of growing and using plant dyes have nevertheless remained in many parts of the world, usually associated with small-scale dyeing of silk, cotton and linen.

- No plants are now grown in the croplands for use as dyes, yet the skills of wild-harvesting and processing plants for craft-scale work have been retained. Natural dyes and dyestuffs can be bought from specialist suppliers.

Dye plants – Introduction

Types of plant, animal and mineral dyes. Dyes in history. Dyes in the croplands. Dyes in the modern world.

Types of natural dye

Natural dyes are derived from three sources – rocks (earth pigments), plants and insects.

Earth pigments – mineral dyes. The ochre pigments – mostly red, brown, and yellow – trace the oldest surviving uses of natural dyes in art and craft. The ochres are found on the earth’s surface in certain types of rock. Because they are mineral, and do not degrade like plant materials do, the ochres survive the years if sheltered in caves or overhangs from natural weathering.

Plant dyes. Colourings come from many different parts of plants. Tap root of dock, tuber of beet, rhizome of iris, leaf of woad, stem of weld, wood of old fustic, flower of chamomile, fruit of blackberry, the whole plant of the seaweed dulce – the list goes on. Dyes are found in many plant families, but the main dyes used commercially for strong colour before chemical manufacture come from the legume family – the nitrogen fixers – indigo, old fustic, brazilwood and logwood among them, and our own dyer’s greenweed, broom and whin.

In past ages, people must have spent many years experimenting with methods to extract colour from plants. They handed down their knowledge from generation to generation. If the knowledge was lost, it would take time to be regained, since the colour of the extracted dye is not obvious from the colour of the plant. The look of indigo or red sorghum plants, for example, suggests no trace of the deep blue and red that can be extracted from them.

Animal dyes. A further category of dyes comes from small animals. Examples include a purple from marine molluscs, various reds and blacks from oak galls (made mostly of plant tissue but caused by insects) and the most widely used animal dye today, cochineal from the female of a scale insect (more at ‘Dye species of the world’)

Natural dyes in history

The people who first explored natural dyes all those thousands of years ago must have wanted to change the way objects looked, whether carvings, rock art or clothing. The existence of dyed material in far antiquity counters the view – too commonly held – that people were then too primitive or too occupied with staying alive to have time to think about colour and design.

Earth pigments survive

The use of orchres and charcoal in cave drawings pre-dates agriculture by a long way. The first agriculture on the north-atlantic coast of Europe was 5000-6000 years ago, but the classic rock art of Europe – including that of the Lascaux caves and the Cave of Altamera was more than three times older; and if crops were domesticated in Mesopotamia or thereabouts 10,000 years ago, then the ancient cave paintings of Australia were more than two-times – probably much more than two times – older (Ed. the age of these paintings is under continual investigation and revision – check with the Bradshaw Foundation web site and national web sites).

Dyed cloth rarely survives

Dyes made from earth pigments survive over time. Not so cloth and other materials made from wool and fibre. And but for a few occasional finds, little would be known. One of these finds is the mummified corpses in the Qizilchoqa graves in Xinjiang, China. They were preserved due to the highly desiccated (dry) environment they lay in for around 3000 years and were found dressed in clothing of astonishing colour and style (Mallory & Mair).

The weave and pattern of that Bronze Age cloth (2000 BC) are said to be similar to those found in the cloths of Iron Age Celtic people of central and western Europe and even to the modern plaids and tartans of Scotland (Barber). The hypothesis has been proposed, though not proven, of a direct line of transmission from the originators of the Bronze Age twills to modern tartans.

So from all this came a knowledge of natural dyes that was handed down to recent centuries, when some of it was preserved in written form and still pertinent today for those wishing to explore our botanical heritage (see the Ciba Review on mediaeval dyes).

Dye plants in the croplands – crops and wild harvesting

Not much survives of the history of plant dyes in our locality over the first few thousand years of farming or earlier. Yet many plants that have been used for dyes in recent centuries have lived in the region since well before farmers arrived here – including iris, oak, birch, tansy, greenweed, dock, lady’s bedstraw, dulse and other seaweeds.

Little is known for certain of whether these plants were actually used to make dyestuffs in stone and bronze ages. Certainly, they were used as such in recent centuries, often at craft scale – an ethnobotany that had almost been lost by the early 1900s.

Dyes as commercial crops, now faded

The three main commercial dyes of the croplands over the past few hundred years are woad, madder and weld, giving blue, red and yellow colours. None was grown over large areas – they were tried and found too difficult, or else the dyestuffs could be imported more cheaply from further south or overseas. In the last 100-150 years they were replaced by tropical dyes, such as indigo for blue, but then the tropical dies were supplanted by industrially made chemical pigments.

All three of woad, madder and weld can be grown easily in our climate – the woad is like a tough cabbage, madder a climbing, sticky relative of the noxious weed cleavers and weld a short-lived, usually biennial, plant of waste ground, industrial sites and waysides.

There’s more on cultivated and wild dye plants in Scotland at Dye plants in the croplands …

Natural dyes in the modern world

Though commercial growing of dye plants ceased in Britain, the use of natural dyes in small scale art and craft has remained. There is a growing interest and a market, especially in dyed fabrics that can command a price for being exclusive, local and natural.

Unlike fibres which, except nettle, are difficult to find and extract in the croplands, many dye plants have remained common in hedges, copses, fields, waterways, seashores and marshy land. Most people no longer realise their uses (or even that they are there), but they are a rich source of interest for people who want to find.

Dye plants are everywhere

Of all the plants examined in 5000 Years, dye-plants are the most common, easily harvested and easily processed. In most instances, the plant material can just be cut into small pieces and boiled. The dye can be used straight away to colour paper or cloth, or more skilfully with a mordant to make the colour stick. (More at Sources … ).

Several posts and articles on the Living Field site in 2021 and 2022 show how local and imported plant dyes are being tried on various materials: see Ruth Black’s Ancient and Modern: techniques with wool in textile art and Jean Duncan’s Making ink from oak galls (and barley and onion skin and …)

The 5000 Years Dye Plants pages will continue at ‘Dye plant species of the world’ …. [in progress], Dye plants in the croplands and Sources references links contacts.

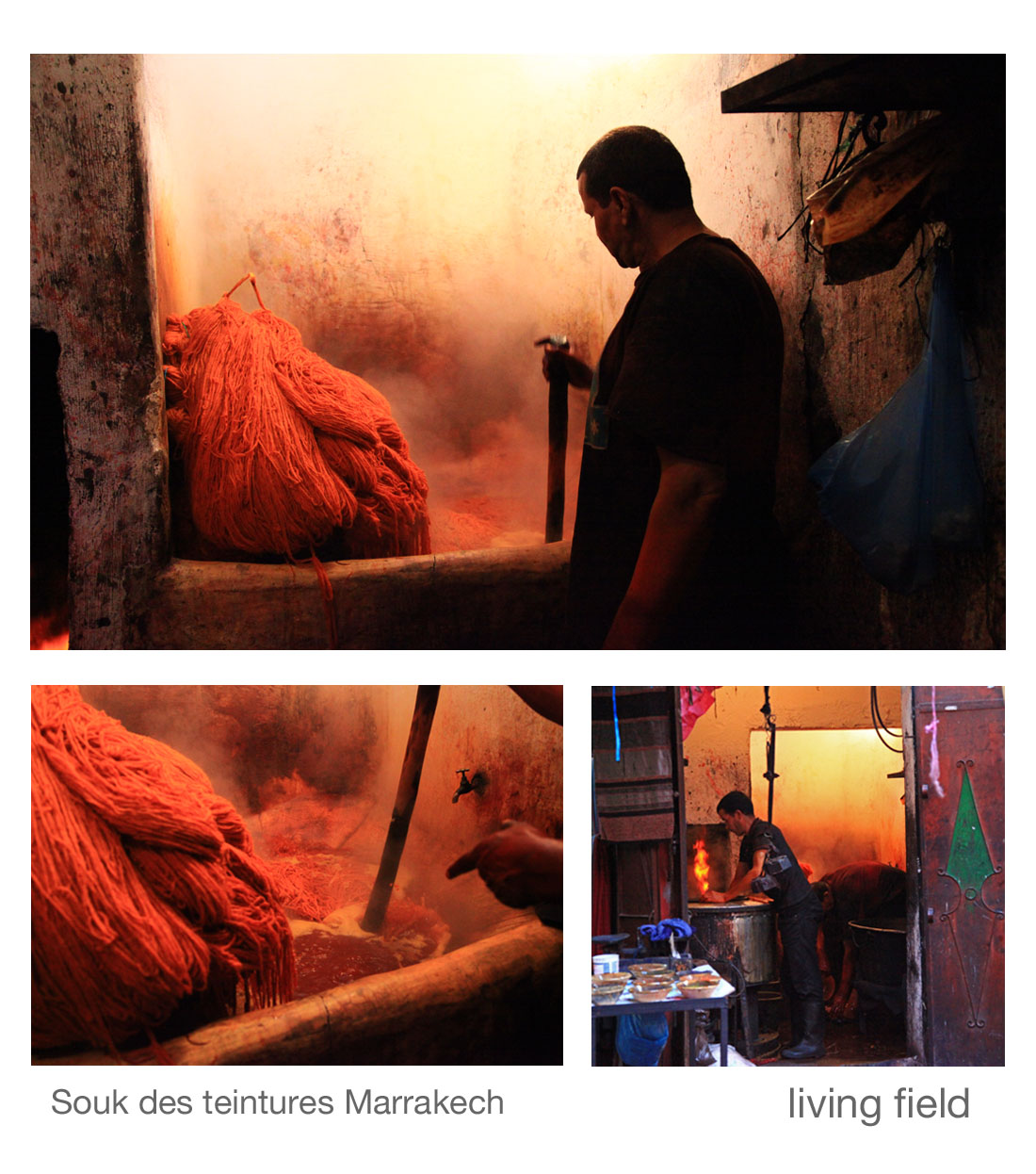

Photographs from the Souk des Teintures in Marrakech, Morroco are shown above and higher up the page. This Souk is alive with crafting in fabric and colour. Outside some workshops, bowls of dyes were arranged for visitors to see – some colours from plants, others of a metallic appearance and probably manufactured. Great bundles of fabric were being immersed and stirred in vats of hot dyestuffs of the deepest colours. This is how it must have been in many textile dye-works before the industrial age.

Contact/author for this page: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com